There was a moment in Rogue One—a flawed, complicated moment, in a film which many people didn’t like—that fundamentally changed what the Star Wars saga is about.

In the final sequence, instead of focusing on individuals, the camera follows the disc with the Death Star plans pass hand-to-hand as Darth Vader chases it down. Someone watching Rogue One has almost certainly seen a Star War, and thus should know that the plans make it through. But the film approaches this moment from the point of the view of the terrified Rebels who are barely, desperately, keeping the disc one step ahead of the enemy. We see that it reaches Leia with seconds to spare, and then she flees with it. And we know that she’s going to be captured in a few minutes, but that the plans will be safe with R2-D2 by then. The Rebellion will survive. The sacrifices have worked. Leia takes the disc and calls it hope.

This is the moment when Star Wars went from being a boy’s story to a girl’s story.

The moment itself is complicated, because the filmmakers used uncanny valley CGI to recreate young Leia, which made the scene as jarring as it was exhilarating. It was also complicated by Carrie Fisher’s death. When I saw it the first time, on opening night, people whooped with joy at that moment. The second time, a week after her untimely passing, I heard sniffles and even open sobs across the theater.

Within the film, however, this scene means that Jyn Erso, a taciturn criminal who only half believes in the Rebellion, has succeeded in passing crucial information to Leia, one of the Rebellion’s leaders. The ragged team of ne’er do wells who broke into the Imperial data bank and hijacked the plans have succeeded: the Resistance is saved, Leia has the plans, and we know that the Death Star will be destroyed. We also know, now, that this raid was led by a complicated, tough, anti-heroic woman—a woman who is never a love interest, never damseled, and who leads a diverse squad of men into a battle. Men who voted her their leader. Men who left the “official” Rebellion to follow her on a suicide mission.

Before this moment, the Star Wars films were primarily stories of active young men, acting either heroically or villainously as the story demanded.

The original Star Wars trilogy is a boy’s own space adventure. We followed Luke on his hero’s journey, we watched him learn from an older man (and then an older male puppet), vie for the role of hero with a roguish scoundrel, and think that he might end up with the pretty girl, only to learn that she was his sister. His arc in each film was set by his father: in A New Hope, he wants to “become a Jedi, like [his] father”; in Empire he seeks vengeance against Vader for his father’s murderer—and then learned that Vader is his father, which, in one moment, changed his conception of himself, his family, and the black and white morality he’d been following; his arc in Return of the Jedi centers on his need to save his father. The boy wins. His father joins the two other male authority figures as a Force Ghost, the boy is now a man—and in all of this his mother only rates a single sentence.

In the prequels, we learn Anakin’s story. He wins podraces, leaves his mother to become a Jedi, trains under two male authority figures, falls in love with a pretty girl, and gradually succumbs to the Dark Side. His fall comes because he is so angry and fearful about the two women in his life—his murdered mother, and his possibly-doomed wife. The Jedi around him tell him repeatedly not to get too attached, and given that his attachments are all to the women he loves, it’s hard to avoid the conclusion that women were his downfall.

This prioritizing of fear over love or lack of attachment causes him to lose his entire family, which is tragic to be sure, but it’s also interesting to note that his mother’s death is about him and the fear surrounding his wife’s death is about him. Even his wife’s death is immediately overshadowed by Anakin’s reaction to her death.

Both trilogies feature the loss of a mother-figure—as Anakin’s mother Shmi is murdered by Tusken Raiders, Luke’s Aunt Beru is killed by Storm Troopers (and in ROTJ, Luke wistfully mentions having no memory of his mother). Both trilogies share a vision of a beautiful, seemingly unattainable girl, of high social class and political training, who accepts the friendship and/or love and/or brotherhood of men from a lower class. Padme is an “angel” to Anakin. Leia is a beautiful hologram to Luke. They were the perfect princesses who filled the “girl slot” in two trilogies about motherless men and their problematic relationship to fathers and father-figures.

And, yes, the two women I’m calling “pretty girls” here are Padme Amidala, Queen and Senator, and Leia Organa, Princess, Senator, and most importantly, General.

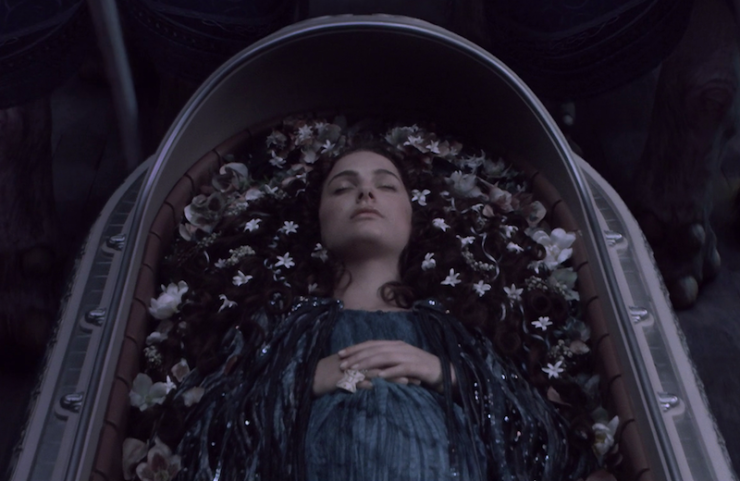

And let’s look at those arcs: in The Phantom Menace, Amidala is a Queen who represents an entire people, and works within the Republic to try to use the law for the good of the people. She’s duped by Palpatine, and gradually her story shifts to one of torment over her forbidden love, facing pregnancy alone, and being emotionally and physically abused by her secret husband—all before she dies (of a broken heart) right after giving birth. In A New Hope, her daughter Leia withstands torture and reveals herself to be a sassy leader, but is gradually softened by love. She is taken prisoner (again), forced to wear a degrading, sexualized outfit, and finally ends the trilogy fully femme, wearing a princessy dress (probably left by a woman the Ewoks ate) with her hair loose. One male lead is now her romantic partner, the other has gone from being a potential love interest/friend, to being safely categorized as her (celibate, probably) brother.

These stories are carved out around the driving force of the trilogies—the stories of Anakin and Luke. We are introduced to the universe through Luke’s yes, and it’s Anakin who gets the dramatic “hero who falls from grace” arc in the prequels. Two generations of girls watching these films had to make a choice between identifying with beautiful, accomplished royalty who were being framed as objects of perfection, or with scrappy guys who were allowed to be witty, earnest, and heroic.

But now The Force Awakens and Rogue One bookend the earlier trilogies with two stories focused on women, highlighting a core of complex women who act in counterpoint to the men.

We meet Rey alone. She lives in the desert. She scavenges, barters her finds, cooks her own meals. She is completely self-sufficient, the way a person would have to be in that life. She meets each challenge the plot throws at her. She’s excited to join the Resistance. Luke’s old lightsaber is passed to her by a woman—an older, independent woman who has a statue to herself erected in front of the casino she owns—and Rey initially rejects it and runs, and is quickly captured by Kylo Ren. Now this is going to play out the same way Star Wars did, right? Her kidnapping will pull Finn into the Resistance (just as Han was originally pulled in to rescue of Leia) and an older, wiser Han will now get to rescue his pseudo-daughter, while also trying to win his son back from the Dark Side.

But that isn’t what happens at all.

Rey, trapped alone on Starkiller Base, does exactly what she’s done her whole life: she fights to survive. She pushes Ren out of her mind, and, having gotten the gist of what he was trying to do to her, turns those tactics against the man guarding her. She sneaks through the base and begins climbing to comparative safety, because she’s spent her entire life climbing in and out of abandoned starships to scavenge and feed herself. She wasn’t raised in a loving foster family like Luke, or by the Jedi order, like Anakin. And then we come to the moment that made me cry in the theater: Finn arrives and fights Kylo bravely, but he doesn’t have access to the kind of power Rey has already displayed. When he falls, my first thought was that Rey would be captured again, as Leia was, and that the second film would be about getting her back. Instead, the lightsaber flies to her hand, not Kylo’s. And she’s able to fight her former captor to a standstill not because of months of Jedi training, but because she’s had to defend herself with a staff while living alone in a desert. You can see it in how she wields the lightsaber—she has none of the educated grace Anakin or Luke did—she’s just slashing and parrying and hoping for the best. But it’s enough to stop her would-be mentor. It’s enough to protect her and Finn until Chewbacca can rescue them both.

When Rey returns from Starkiller Base, knowing that she couldn’t save Han, and only barely saved Finn—again, the two men who charge in to try to rescue her, and whom she then had to rescue—it’s Leia who welcomes her into the Resistance with an embrace. It would have made more sense, in a certain way, for Poe and Rey, the new generation, to rush Finn to the clinic. It would have made sense for Chewie and Leia to mourn Han together. But this scene isn’t about that. Leia’s known Han was dead since the instant it happened. She also knows that once again a young woman has been thrown into a particular type of life, has seen things no one should see, and that she needs the strength to keep going.

It doesn’t matter if Rey is a Skywalker (I sincerely hope she isn’t) but in this moment, as the two fall into each other and hold each other up, Rey becomes part of the circle of women who have kept the Rebellion, and then the Resistance, going.

A woman stole the plans, and passed them on to another woman, who then welcomes another woman into the new resistance.

With Rogue One and Jyn Erso, we get a new twist on the old story: a small girl sees her mother die and is separated from her father, and must fight to either save him or redeem his legacy. But this time, it’s an angry girl doing it. She may have been trained by Saw Gerrera in the past, but she uses her own wits and fighting skill to get her team to Scarif. What she has, just like Rey, is determination. She doesn’t fold and give up when the Rebellion’s leaders vote against her idea. She doesn’t allow injuries and physical exhaustion to stop her from getting to the transmitter. Even when Krennic turns up at the last minute like Jason in a Friday the 13th film, she’s ready to fight him if she has to before Cassian Andor shows up to help.

In Rogue One, it’s also Mon Mothma, one of the leaders of the Rebellion, who first works to get Jyn Erso heard. When her idea to get the Death Star plans is voted down, Mon Mothma can’t go against the free vote, but she looks the other way while Jyn leaves, and she does mobilize back-up once it’s clear the Rogue One group have infiltrated the Scarif base.

Over the last few years Star Wars has gone from being a story of boys fighting and finding themselves with gorgeous royals as side characters, to a story that features princesses who are also career military, rebels who leave the past in the past and sacrifice their lives to get shit done, high-femme queens who try to promote peace from the inside, scavengers who answer the call to adventure, elderly business magnates who celebrate themselves with statuary.

The Force Awakens and Rogue One transform the entire arc of the series, shifting from stories of young men acting more or less individually, to focus on women building resistances against unfair power structures, working together with people across class and species lines, welcoming new members, honoring each others’ work. Women have passed the spirit of the rebellion to each other, from Padme and Mon Mothma’s co-founding of the Rebellion, to Jyn Erso’s sacrifice, to Leia’s leadership, to Rey’s taking up the search for Luke. These stories may have happened a long time ago, but the future of Star Wars is female.

Leah Schnelbach can’t wait to see Rey in training! Come talk to her on Twitter.